With fentanyl deaths on the rise, south metro police, advocates grapple with solutions

From his vantage point as a toxicologist in the emergency departments of UCHealth’s Highlands Ranch and Anschutz locations, Dr. Kennon Heard said fentanyl is easily the most common drug involved in the overdoses he treats.

“This is going to be on par with seeing a stroke or a heart attack,” Heard said, estimating overdoses are treated multiple times a week, if not daily. “It’s that common of an event.”

Heard sees both people with substance use disorder and, more frequently, people who are occasional users and often think they are taking a drug other than fentanyl.

“The change is probably that we’re seeing a significant number of people … who get something they think is a pharmaceutical product,” he said.

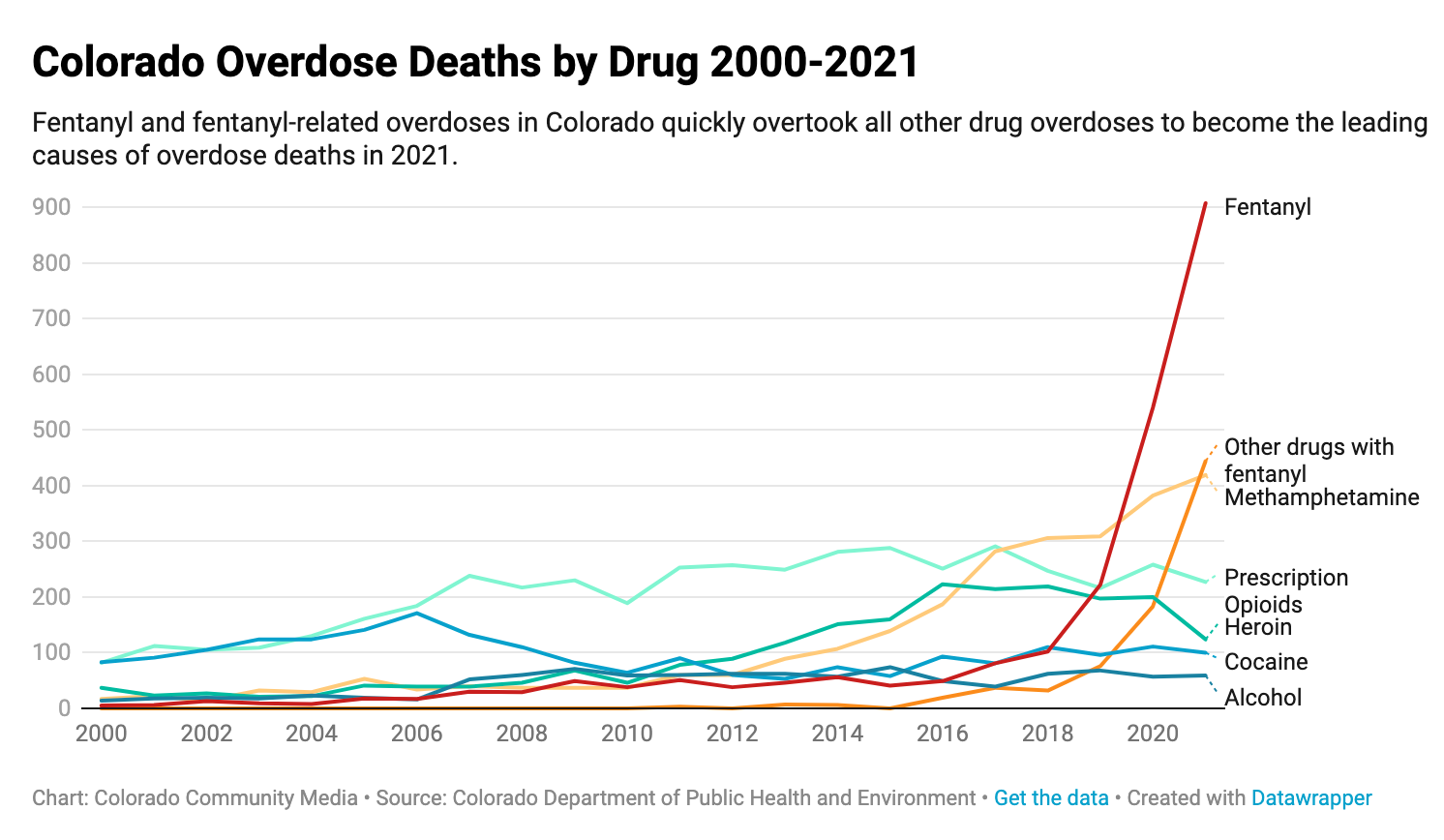

Fentanyl’s presence in Denver’s south metro region, and Colorado, has continued to increase over the past five years — but the numbers have skyrocketed since 2020, when the drug overtook methamphetamine as the leading killer in Colorado, according to data from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE).

The growing ubiquity of fentanyl in the drug market is also reflected in the increase of overdose deaths in the south metro area from 2015 to 2021, CDPHE data shows.

In 2021, Arapahoe County reported 101 fentanyl-specific overdoses, which make up 56% of all reported overdoses that year. That number is a sharp increase from 2020 when there were 69 fentanyl overdoses, accounting for nearly 47% of all overdose deaths, though fentanyl was still the leading drug for overdoses that year.

Douglas County saw its biggest spike in fentanyl overdoses in 2020, with nine fentanyl overdose deaths that accounted for 18% of all overdoses that year. Numbers in 2021 were similar with seven fentanyl overdoses, making up 16% of overdoses.

It’s left law enforcement and harm reduction advocates at odds over how best to respond to a mounting crisis that took the lives of more than 900 Coloradans last year. And the state’s new law, the Fentanyl Accountability And Prevention Act — which went into effect July 1 — is set to once again test the theories of criminalization versus risk mitigation for drug users.

A growing emergency

For area police, the crisis is daily.

“I would say that fentanyl overdoses have exploded,” Englewood Police Sgt. Brian Cousineau said. “If not daily, every other day we’re dealing with something related to an overdose.”

A synthetic opioid, fentanyl is said to be 50 to 100 times more potent than heroin or morphine, according to the CDC, with a potentially lethal dose being about 2 to 3 milligrams. Part of what has made the substance such a threat is its presence in nearly every opioid available on the black market.

“It’s everywhere,” said Cousineau, who said fentanyl is frequently found in “blues,” slang for drugs such as Valium and Xanax, which are typically used to treat anxiety, insomnia, and seizures.

But fentanyl has also made its way into heroin, meth, cocaine and MDMA — more commonly known as molly. Since fentanyl’s presence has cast such a wide net — from black market prescription drugs to popular recreational substances — and because of how cheap it is to mass produce, law enforcement is seeing the drug threaten a spectrum of people who are young and old, regular and irregular users.

Douglas County Sheriff Tony Spurlock said a majority of overdoses police are responding to involve fentanyl mixed with another drug, such as cocaine.

“Douglas County is an upper-middle-class community and we’re seeing it in that community, finding people in their homes,” Spurlock said. “It’s not the image people conjure up when you think of a drug abuser.”

Data provided in April show narcotics and drug violations were up 28% over last year in Douglas County, Spurlock said.

District Attorney John Kellner, who heads the 18th Judicial District based in Arapahoe County, said the time is now to impose harsher punishments on dealers of fentanyl — and other potential fentanyl-carrying drugs — in a bid to curb overdoses.

“Our approach is to go after the dealers and suppliers and hold them accountable,” Kellner said, adding that his office is pursuing “significant prison sentences” for producers and sellers of the drug.

Kellner recently touted what his office called a large-scale drug bust in May that led to the seizure of 200,000 fentanyl pills along with 9.4 pounds of heroin, a kilogram of cocaine and four guns. It also resulted in the indictment of eight people believed to be involved with drug trafficking, Kellner said.

That announcement was joined by one from Brian Besser, special agent in charge of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s Denver Field Division, who said his office had aided in the “largest fentanyl seizure on any U.S. highway,” when state patrol officers found 114 pounds of fentanyl powder in the back of a vehicle on Interstate 70 traveling toward Denver.

But the seizure, which took place in June, failed to produce law enforcement with its greater goal: the suppliers.

After initially agreeing to lead DEA agents to supposed kingpins in South Bend, Indiana, the driver evaded authorities and escaped, a detail Besser did not mention during a July 6 press conference detailing the bust. It only came to light after a story from the Denver Gazette, which obtained the driver’s arrest warrant.

The vast majority of prosecution has instead fallen on low-level dealers and users.

Need for harm reduction

The criminalization of fentanyl, and all drugs, has only led to worse overdose outcomes, said Lisa Raville, executive director for the Harm Reduction Action Center.

“We’ve never been able to arrest our way out of drug use … all it’s done is put us in the overdose crisis that we’re in as well as led to unsafe drug supplies,” Raville said.

The action center, based in Denver, works with drug users to reduce their overdose chances and make drug use safer. The nonprofit organization’s multi-pronged approach includes providing clean syringes for safe injection, supplying users with drug and HIV testing, getting users access to life-saving naloxone and engaging in community outreach and education.

The center sees about 75 to 125 people per day, according to Raville, with about 12,000 people who’ve signed up for its services over the past 10 years.

A staunch supporter for harm reduction policies and practices, Raville said she is discouraged with the direction law enforcement has taken toward fentanyl, which she feels has been spurred by the state’s new law.

“We feel that the messaging in law enforcement has actually gone backward,” Raville said.

Along with more emphasis on law enforcement-led investigations into opioid use and deaths, the law will also require emergency medical providers, coroners and law enforcement officials to participate in a state wide program to map overdose deaths. Raville fears this could dissuade more people from calling 911 for help with an overdose as it will likely attract more police attention.

“We can’t count on the fact that law enforcement won’t come,” Raville said.

But perhaps the most consequential decision by Colorado lawmakers was to drop the amount needed to charge a felony for fentanyl from 4 grams to 1. That’s the equivalent of about 10 pills, according to Englewood Sgt. Cousineau. Raville said the law now puts many of her clients at major legal risk as most carry between five and 20 pills on them at a time.

Instead of pursuing criminal charges, Raville said the key to combating the fentanyl crisis is providing more resources to drug users, from testing to a safe supply of drugs.

In an effort to build more resources for addiction in Douglas County, Racquel Garcia founded Hard Beauty, a peer recovery group that started virtually during the pandemic and recently opened a brick and mortar location in Castle Rock to offer the area’s first community recovery center.

“I want all options to recovery to be in one space to allow people to figure out what’s best for them and recover,” Garcia said of Hard Beauty’s mission.

The impetus for Garcia to offer peer recovery services came from her own experiences trying to get sober, she said. Garcia found few resources outside of Alcoholics Anonymous and Celebrate Recovery groups, which didn’t work for her. Ultimately, she found help at Parker’s Valley Hope, a residential treatment center.

“It just felt like we could do better and actually I knew we could better,” she said. “I want to open up the space and discussion of recovery to make it big. Especially in high affluence areas.”

Hard Beauty is also working to obtain housing to help provide sober living and recovery support past the initial rehab period.

“Even if the cops can get you to jail or treatment, if you want to live in a sober environment, there’s no supportive housing in Douglas County,” she said. “You need long-term support for long-term change.”

The state-wide law does make some inroads for harm reduction policies, with $19.7 million for a bulk purchase of naloxone (a common brand of which is Narcan), $10 million for treatment centers and $600,000 for fentanyl testing strips.

But lawmakers should go further, said Raville, and allow for safe injection and smoking sites for drug users where they can be aided by trained medical staff to avoid an overdose.

“We need to be innovative and we need to be using evidence-based solutions,” Raville said, adding that such a proposal has been piloted in other countries and has helped drive down overdose rates.

Looking for solutions

Police in the south metro area said while they’re obligated to enforce the laws around fentanyl they also see the benefit, and need, for harm reduction approaches.

“My job isn’t to judge how the person got into the position that they are in, my job is to get them care,” Littleton Police Sgt. Brant Dimoeck said. “The average person that we talk to … they’re not bad people. They have an addiction. They have an issue.”

Sheriff Spurlock said he agrees with the importance of addiction treatment as a tool, noting there are few resources available in jails for people with substance use issues. Drug rehab programs are a possibility, but medicated-assisted treatment, one of the more successful recovery tools, is typically not offered.

“Our jail is not designed for that,” Spurlock said.

Increasing treatment facilities would benefit law enforcement, not only by alleviating burdens on jails, but also by helping to prevent crime, Spurlock said. However, Spurlock still thinks law enforcement has an important role when it comes to responding to drugs in the community.

In Spurlock’s experience, there is significant overlap between people arrested for drug violations and people arrested for property crimes.

“If you have significant and adequate facilities for treatment, you will reduce crime,” he said. “But it’s also important to remember there are individuals out committing multiple crimes so that they can feed their habit and they have to pay for that behavior.”

When responding to someone who may be overdosing, police said medical attention takes priority.

Naloxone, which is a quick-acting antidote for overdoses, is used frequently to revive individuals, police said. Spurlock estimates Douglas County officers are having to use naloxone on a weekly basis.

Arrests are typically not made during these encounters, according to Englewood Sgt. Cousineau, so long as the individual overdosing has no more than a “personal use amount,” which is 1 gram of fentanyl — about 10 pills. The drug is usually confiscated and destroyed, Cousineau said.

“Part of it is compassion, we don’t want to put criminal charges on somebody who is in a state of distress,” he said.

Arrests can follow when an individual is found with more than one gram as well as when someone experiencing an overdose also commits other crimes in the process, such as causing a car accident, according to Cousineau.

But officers said they alone can’t always respond adequately to a situation. It’s why departments across the region, including Englewood, Littleton and Douglas County, have turned to co-responder programs to link police with trained clinicians when responding to certain calls, such as mental health concerns and drug use.

Officers said those trained professionals are able to better connect to, and build trust with, certain individuals in distress better than police can. Co-responders are also able to connect individuals with resources instead of jails, something DA Kellner said his office has also pursued.

The DA’s diversion program allows some people charged with drug possession to funnel into rehabilitation treatments that — if deemed successful — could see their cases dismissed or significantly reduced.

“This is not the justice system of the ‘80s and ‘90s,” Kellner said. “It’s an all-above approach that’s going to solve this problem.”

According to 18th Judicial District spokesperson Eric Ross, 104 cases have been referred to the program, with 28 successfully completed, Ross said data on “failures versus those that are still in process,” is not available.

However, that option remains limited because of the lack of programs or facilities in the region offering addiction services. Spurlock said Douglas County is reliant on partnerships with treatment programs or facilities in Denver.

But, for Raville, believing that law enforcement will be enough to wean the majority of individuals off drugs is fantasy thinking.

“People have been using drugs forever and ever and people will continue using drugs forever and ever,” Raville said.

Instead, Raville wants to see more honest conversation and education around drug use and how to be safe. She believes broad legalization, such as what has been done in Portland, Oregon, will create a safer supply for hard drugs that fentanyl will not be able to permeate.

“We have a safe supply in the United States right now, it’s called alcohol,” Raville said. “The United States has never done a good job of talking about drug use.”

Reporting by Robert Tann and McKenna Harford. Published on ColoradoCommunityMedia.com.